This is the first-person account of a U.S. Forest Service employee who was a passenger in a Hiller 12E helicopter when the collective control linkage became disconnected at the rotor hub and the aircraft started an uncontrollable climb. The passenger climbed out of the airborne helo, managed to reconnect the linkage using the awl of a Leatherman Tool, and held the makeshift repair in place until the chopper could land safety.

Aviation Safety Communique

Reported by: USFS, Ochoco NF, P.O. Box 490, Prineville, OR 97754

Event: Date: 02/13/97, Local time: 1545, Injuries: no, Damage: no

Location: North Fork Crooked River, Oregon, along Forest boundary T15S R21E

Mission: Type: elk census (recon), Procurement: OR Dep't. of Fish and Wildlife, Persons onboard: 3

Aircraft: Hiller 12E

Narrative

I was asked to assist the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) conduct a census count on elk using a Sightability Model developed by Idaho Fish and Game. The model was designed to use a reciprocating engine helicopter with two observers and the pilot. ODFW had run into a pinch using their own personnel and on Thursday afternoon (2/13) they could not get two of their employees to fly. I had cooperated all along with ODFW in this process to try and procure accurate population estimates of elk occurring on the Ochoco National Forest. I was being asked to fly in an "un-carded" aircraft and I knew it before departing.

I was asked to meet the fuel truck 4 miles up Teter's Road at approximately 1200. When I arrived at the meeting place, the helicopter was finishing the morning's census areas. I talked to the fuel truck driver (Ellen, the pilot's wife) about the helicopter and the pilot (Philip) to satisfy my own safety concerns. I found out he was FAA part 135 certified and had contracts with APHIS for conducting aerial coyote control. I also established the fact that we would be flight following with Ellen during the afternoon survey.

We started the elk survey at approximately 1400. We surveyed one census unit of about 4,000 acres and then started a second unit. We had been in the air approximately 1 1/2 hours when Philip suddenly said, "We have a problem." I was not initially concerned and said, "You will have to land it, right?" He then replied we had lost the collective and could not land and the problem was a serious one. The collective control linkage rod had come disconnected at the end where it connects to the collective arm at the main rotor shaft.

Losing the collective will cause the helicopter to gain altitude since the blades were at full pitch. I was sitting on the left side of the bubble (the side where the linkage rod is located on the helicopter) and Philip said our only chance of survival was if I got out and tried to push up on the collective arm to adjust the blade pitch, reducing lift from the rotor blades. I unbuckled from the seat, opened the door and carefully stepped out onto the skid. I wrapped the shoulder harness of the seat belt several times around my left wrist. I kept a hold of the seat belt with my left hand. I found that I could not reach the collective linkage unless I let go of the seat beld and climbed up from the skid onto the cargo basket.

I had some communication with Philip since I kept the headset on. It was very difficult to communicate, though, because of the rotor, engine and wind noise. I heard him tell me to push the collective arm up slowly. I tried to do this and the helicopter fell violently (Philip estimated more than 100 feet). Philip and the passenger (Meg, ODFW employee) yelled to pull the other way so I pulled back down on the collective arm and the helicopter stopped falling. I have no idea why I did not fall off the helicopter at that point.

I said if they (people in the helicopter) could find some sort of pin, I may be able to reconnect the linkage arm. They said they had nothing. Philip then said to pull down on the collective arm. We found that if I pulled down VERY hard, we would shed elevation very slowly. But I couldn't pull down hard enough for a long enough time to significantly lower the helicopter's altitude.

Philip had the helicopter in full forward speed to slow our ascent. He later told me he had the rotor RPM's 100 lower than red line and we had a forward speed of 100 knots, 10 over maximum I guess. I rapidly started to get VERY cold, since the outside air temperature was about 20 degrees. The wind force had blown a contact out of my eye and my hat and sunglasses off. I also lost both gloves, because I used them over the collective arm to try and pull harder. I asked if there was something I could use to pry down on the collective lever and Meg handed the fire extinguisher out. I tried that a little and felt unstable pulling on it. I thought the fire extinguisher could go through the tail rotor, so I threw it down with force to get rid of it. The whole time the pilot communicated the urgency of the situation by calmly saying, "You've got to do it buddy or we are going to die."

We had been into the problem about 15 minutes when Philip contacted Ellen and advised her of the problem. Ellen then phoned the Prineville airport and asked that the Oregon State Police be advised.

I was rapidly losing strength and mobility in my hands. Philip remembered he had a "Leatherman Tool" in his first aid kit. Meg rummaged around and found it and handed it out to me with the file part opened. The collective linkage rod had a bearing-like ball in the end of it with a hole in the ball. Because of the vibration of the rotor, engine and wind, the ball was moving around in circles, making it difficult to start any sort of makeshift pin unless it was pointed. I handed the Leatherman back in and asked Meg to open the leather awl part, which had a pointed tip.

I noticed we had gained enough altitude that we were getting into the clouds. Philip said we had gotten to an altitude of 9,500 feet . . . about 5,000 feet AGL. He also said the carb temp had dropped dangerously low, as had the fuel quantity.

When I got the Leatherman tool back with the leather awl opened, I first tried to get it started with my right hand since I am right handed. The forward air speed must have been too great, because I tried many times to get it started and I could not bring my arm forward accurately. I switched the tool to my left hand to attempt aligning the leather awl and have the wind from our forward air speed help push my hand toward where I was working. I could not really feel the Leatherman Tool, since I had lost feeling in my hands from the cold. I was getting VERY frustrated and angry, because I could not get the awl started into the linkage rod. Philip and Meg helped me focus and keep trying by constantly saying "You almost got it" and You can do it."

After several tries, I got the leather awl started. I wiggled it in as much as I could and at the same time I heard Philip say, "We are going to live!" I knew I barely had the point of the leather awl started into the linkage rod. I held as much inward force onto the Leatherman Tool as I could muster so it did not slip out. Philip descended now that he had collective control and we quickly landed on a scab flat near the Forest Boundary. I had to stay outside the helicopter to hold the tool in place through the entire descent to landing. He made a VERY soft and normal landing. Philip notified Ellen by radio that we had landed OK. Meg had glanced at her watch when the incident started and when we landed. The time from the start of the problem to landing was approximately 25 minutes.

After we collected our wits and assessed our location, we started figuring how we were going to get out. I had gotten my hands warmed up and quenched a great thirst by eating snow. We decided it was a long walk out and there was no road access due to snow depth. Philip had discovered the linkage bolt when we was inspecting the aircraft after we landed. It had fallen into the engine pan. He could not find the nut that went into the bolt. Philip put the bold back through the linkage (which he said was difficult to insert on the ground with the engine off). The bold had a hole in it for a safety wire. Meg mentioned that she had seen a safety pin in the first aid box. We thought that if we put the safety pin through the hole in the bolt, it should hold it in place, enabling us to fly the helicopter back to the fuel truck. Philip put the safety pin into the end of the bolt and instructed Meg to keep her eye on the pin. If the safety pin came out, Philip thought he could land the helicopter before the bolt came out. Philip started the helicopter again and we flew it back to the fuel truck without any further events. After Philip installed the proper lock nuts on the bolt, he and Meg flew the helicopter back to Prineville and I rode back in the fuel truck with Ellen.

I have some personal observations about this incident. First, it may seem easy to say I had a cavalier attitude toward the aviation policies in place with the Forest Service. To an extent, I did have some question about the need and legitimacy of several of our aviation policies. Also, there were other reasons why I did not follow our policies that day. I believe that many employees face the same situation I did regarding choices in flying in aircraft not approved for our use. I know I have faced making this choice many times during my career and most times I have not participated in the flights. I was faced with a choice of getting the job done, a real need by ODFW for me to help them and with fostering a cooperative attitude with another agency. I made the wrong choice, but at the time it seemed the correct one to me. Second, a team effort determined the outcome of this situation. All people involved retained a cool head and a positive attitude toward the eventual outcome. It would have been very difficult to accomplish my task if people inside the helicopter would not have been so cool and supportive. I also think that Philip must be an excellent pilot to maintain a stable aircraft through several difficult moments. The main reason I was able to stay on the aircraft for nearly 1/2 hour was because of the in-flight stability of the helicopter. There are no "heros" in this story, just people doing what was necessary to get the job of survival done given the circumstances. Lastly, I would like to comment on feelings in a situation like this. I can only offer my own feelings. I never felt the feeling of fear during the incident. I had some frustration and anger at not getting "the job done" quicker. I would like to think most people faced with a similar situation could react similarly. Mabye the adrenaline rush is what keeps fear from creeping in. Anyway, I hope no one faces something like this, but it is reassuring to know that the body can still function in a difficult situation like this.

• Saved By A Leatherman Pocket Tool

• Dear Diary

HER DIARY

Tonight I thought he was acting weird. We had made plans to meet at a bar to have a drink. I was shopping with my friends all day long, so I thought he was upset at the fact that I was a bit late, but he made no comment. Conversation wasn't flowing so I suggested that we go somewhere quiet so we could talk. He agreed but he was quiet and absent. I asked him what was wrong; he said nothing.

I asked him if it was my fault that he was upset. He said it had nothing to do with me and not to worry. On the way home I told him that I loved him, he simply smiled and kept driving. I can't explain his behavior. I don't know why he didn't say I love you too.

When we got home I felt as if I had lost him, as if he wanted nothing to do with me any more. He just sat there and watched T.V. He seemed distant and absent.

Finally, I decided to go to bed. About 10 minutes later he came to bed and to my surprise he responded to my caress and we made love, but I still felt that he was distracted and his thoughts were somewhere else.

He fell asleep - I cried. I don't know what to do. I'm almost sure that his thoughts are with someone else.

My life is a disaster.

HIS DIARY

Made the worst landing of my life today, but at least I got laid.

Labels: diary landing

• Harbor of the Sun

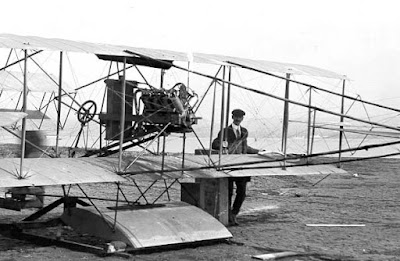

Reading a photography/guide book about San Diego I stumbled on a reference to Joe Boquel who tried, on November 5th, 1915 , to do a "corkscrew" by the Cabrillo Bridge, the entrance to Balboa Park. He crashed and died five minutes before he was supposed to be awarded the Panama-California Exposition Gold Medal. He was not the first, or the last aviator to die in San Diego, a city that once billed itself as 'The Air Capital of The West.' This photograph was taken just before the fateful flight.

Excerpt from Harbor of the Sun—The Story of the Port of San Diego

By Max Miller, Country Life Press, 1940

Someday, perhaps a century from now, North Island and what it represents to our baffling span on earth will be explained. Our period through the childhood of aviation will be dissected by professors. And mankind will know then whether we were another Children's Crusade speeding the way to our own finish, or whether our period was another Renaissance, or whether we were merely out for a good time learning better ways of bombing one another.

North Island, occupying the center stage of the harbor, is a body of land completely surrounded by planes and submerged under planes.

A condensed history of flying was enacted there, is still being enacted there, and the patron saint of North Island is Glenn Curtiss.

He arrived in San Diego in 1910 with an exhibition team. What little flying was being done elsewhere in those days was being done in the morning, the afternoons being considered too windy. But to his surprise he found the San Diego afternoons rather calm and the mornings ideal for his work.

Instead of hauling his exhibition team out of town that night, he made a formal request to be granted the use of North Island for three years and the privilege of erecting the necessary plant for conducting a school.

Since that day North Island has not seen a moment without planes, be they the old pusher type, the tractor type, civilian, army or navy until today all the planes of the aircraft squadrons of the battle fleet are serviced there and housed there.

Because of North Island the current generation of San Diego (this is, those born within the past thirty years) has been deprived of that thrill which comes with seeing one's first flying machine land in town.

But the current generation has not been deprived of watching adults sneaking up on sea gulls, then frightening them at close range, the better to study the mechanics of wing structure and quick take-off. North Island has not had its day: North Island is still having its day. But North Island is no longer the home of fanatical individualists like that wild-eyed Swede, Ivar T. Mayerhoffer, with his home-made contraption, "The Flying Whale"; nor the home of the world's first loopist and the world's first upside-down flier, Lincoln Beachey.

North Island no longer has those day-long arguments over which method of instruction is the better, the "Wright Method' with its dual control, instructor and pupil riding side by side until the student could pilot the ship himself maybe or the "Curtiss Method," in which the student alone in the plane hopped and hopped and hopped until he could hop without crashing maybe.

For that was North Island.

That was the North Island of 1910 and of 1911 and of 1912. That was still the North Island when Glenn Curtiss made from there (in 1911) the world's first seaplane flight.

And when Major T. C. Macauley from North Island made the world's first night flight. Both the army and the navy already were represented among the students. But it was up to Curtiss to interest the navy even more. This he did with the seaplane. For until he actually took a plane off the water, the admirals in Washington remained convinced that aviation was an army game.

Today, of course, all of North Island, once held by the army for flying, is now held by the navy exclusively. The army is out. And such is life.

But if Curtiss, flying off North Island, showed the navy that planes could be taken off the water, Eugene Ely in the same month went one better by showing the navy that a plane could be landed on a deck. He landed on the deck of the cruiser Pennsylvania. Lines and sandbags were used as arresting gear on a wooden platform over the quarter- deck and after-turret. This was the beginning, during the January of 1911, of the modern aircraft-carrier equipment.

During the early flying days on North Island the saying was prevalent that no flier ever lasted more than three years. There seemed reason for this remark, for the year 1913 was an especially ugly one for accidents.

Lieutenant L. E. Goodier, the first army man to have made a flight on North Island, also was the first army man to crash there. He was badly injured while attempting to turn too close to the water in a flying boat.

Two months later during the same year of 1913 Lieutenant Rex Chandler, Coast Artillery Corps, was killed after falling into the bay. The next month Lieutenant J. D. Park was killed. And then Lieutenant E. L. Ellington, cavalry, was killed. And then Lieutenant H. M. Kelly, infantry.

Considering the few planes in use, these army deaths on North Island during one year seemed such a frightful price to pay that a study of the accidents was made a study which resulted in the belief that some of the fatal accidents would have been merely forced landings had the engines not been in the rear of the pilots. In the case of a bad landing, the engine was knocked loose from its supports and fell upon the occupants of the machine.

This hoodoo year of '13 was the year when Sergeant William C. Ocher coined the phrase that has stuck to North Island all these years. He said he would rather be "the oldest pilot in the army than the boldest." Apparently he lived up to it, for, twenty years later, while still on duty, he was awarded a thousand dollars by the government for safety inventions used in blind flying.

In the same manner that the phrase is an heirloom on North Island, so too is the copy of the first army flying rules posted over there. The rules included:

- Do not take up aviation if you expect to be married soon or are in love.

- Horses will be tied to the picket line provided for private mounts and not to trees, fences, water pipes or buildings.

- Dogs without collars and muzzles will be shot.

- Do not enter this branch of the army lured by hopes of increased pay. Expenses are high and there is no use trying to conceal the fact.

- If you are the sort of person who likes to keep his hands clean, don't take up aviation.

- If you are a bluffer, don't take up aviation. You cannot expect to bluff the atmosphere, etc., etc.

The reason for the fourth item was illustrated by the case of Captain B. D. Foulois (later a major general and head of the Air Corps). When funds on the island were low, he fished from his own pocket $150 to maintain the upkeep of his army plane.

Another sad case was that of "The Old Forty-niners," so named because there were forty-nine of them. They comprised a North Island detachment sent to Honolulu to establish an army aviation school there. In Honolulu their hardships were increased because for two years this detail had no planes, and the infantry in Hawaii would not let the fliers forget the fact. They were called the "Walking Aviators."

The saying goes that North Island though today so complicated, so machinelike, so guarded, so serious, so tremendous has furnished more news stories to the world per square foot of land that any other island. It is just a saying. And yet, like all sayings, there is something in back of it, certainly.

Civilians, in glancing across the bay at North Island today, see a baffling land of hangars, shops, factories, run- ways, landing fields. All is complicated, all is secret, and all is beyond a lone man's comprehension.

Records perhaps are being broken, but we know nothing about them, and are not supposed to know anything about them. Individual fliers have been swallowed into what it takes to make The Whole. Even they, the best of them, are but part of some- thing else. Even they today are machines, and over them today giving orders are other machines. North Island is still North Island, but the personalities on it have been transfixed into A Personality. Cameras are not wanted, or crowds, or headlines or volunteer aid from the little boys around town.

But how different it all was on North Island when, on March 28, 1913, Lieutenant T. D. Milling, flying a Burgess tractor type, created a new world's record for two- seater by remaining aloft four hours and twenty-two minutes.

How different when, on Christmas of that same year, Lieutenant J. E. Carberry and Lieutenant W. R. Taliaferro established a new American altitude climb for pilot and passenger. They climbed to seven thousand feet.

How different when, in 1911, Galbraith Rogers arrived from New York in a Wright Model D, the first trans- continental flight. Forty-nine days.

Or when, in 1912, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) John Towers established above North Island a new world's endurance record for seaplanes. He was aloft six hours and ten minutes. He was, incidentally, one of the first students on North Island, arriving for the class of 1910-11. In one of his early flights he was thrown from his plane when it hit a "bump." The plane at the time was at two thousand feet, but he caught hold of the landing- gear framework. Although his legs were swinging in mid- air he pulled himself up and climbed back into the pilot's seat.

And, too, the excitement on North Island when R. E. Scott, formerly an army officer, showed a device with which he said he could drop bombs with "an approach to mechanical precision." He was asked to prove it. He did, for the world's first time, on that April morning of 1914. He made four hits out of five from an altitude of eight hundred feet.

His pilot over North Island was Lieutenant T. F. Dodd, who, with Sergeant Marcus, already had been headlined for having just completed a cross-country record by flying 246 miles in four hours and thirty-three minutes.

And that same year from North Island, Lieutenant H. L. Muller, flying a Curtiss tractor, established the altitude record for "all future time" by reaching 17,441 feet. But what does remain permanent about the record today was his finding that the air above San Diego after he had reached ten thousand feet was warmer than on the ground. This feature of San Diego's air still holds true, naturally, the peculiarity being due, it is said, to the heat waves circulating from the desert back to the ocean.

The civilian students on North Island included the first Chinaman to learn to fly. He was Tom Green, who later became a captain in his home country. And there was Miss Tiny Broadwick, the first person to show San Diego a parachute jump. She flew over the San Diego exhibition and, after jumping, landed far beyond sight of the exhibition grounds. Next day she did it again but better.

Yet long before this, among the earliest, was the Swede, Ivar T. MayerhofFer, and his creation, "The Flying Whale."

Perhaps every town at some early time has had a Mayerhoffer. Perhaps he is no exception. For a Mayerhoffer creates no records, he originates no lasting stunts to be duplicated by a school of fliers. Yet each time a Mayerhoffer takes off he produces a miracle; each time he lands he produces another one.

Perhaps every town at some early time has had a Mayerhoffer. Perhaps he is no exception. For a Mayerhoffer creates no records, he originates no lasting stunts to be duplicated by a school of fliers. Yet each time a Mayerhoffer takes off he produces a miracle; each time he lands he produces another one.San Diego's Mayerhoffer operated his ailerons by a contraption fitting over his shoulders like a yoke. "I can't get used to it," he would say. He would say this ahead of time even to prospective customers. He did not have many, but he had the whole town for his gallery. He charged his passengers "five dollars a throw" the phrase at the time being more accurate than slangy.

His craft was the first commercial seaplane to be operated on the Pacific Coast. For his power he used the remnants of a Roberts two-cycle, six-cylinder motor. The hull, made out of boards, had so much suction that even the harbor was hardly large enough for a take-off. But once he managed somehow to get off he would fly over North Island against strict regulations. The year was 1914-15.

"Swede's going to fly today! Swede's going to fly to- day!" The information had a way of spreading, and the ambulance would come down to the waterfront.

To curb him, a patrol boat was stationed at the narrow entrance of the first of his runways between two piers. This bottled him up for a while, but not for long. He changed his runway. These piers have since been torn down, but in the days of Swede Mayerhoffer the rickety piers were always crowded with spectators. For he was always around there, either repairing his craft from a crash or taking off for another one.

Merely to land on the water shook the seaplane up enough, but he had a bigger ambition. He began landing his seaplane on land. He built a landing runway of greased boards, and he would try to shoot the ship up these.

In one of his crashes a woman passenger was drowned. In another crash he plunged from four hundred feet, striking the bay. The plunge seemed to have been straight down, but it could not have been, for he lived, and he managed to keep his motor afloat.

The Swede told Joe Boquel, whose name at the time was surpassing Lincoln Beachey's, that Joe was a fool not to get more money for his stunts, as he was certain to be killed.

Joe answered: "Who in hell are you to tell me I'll be killed? You're due next, you know."

The Swede, however, was right. Joe Boquel did go first. He was killed a few weeks later while stunting for the San Diego exhibition. Mayerhoifer lasted another year, eventually being killed near Los Angeles, struck by his own propeller.

For San Diego, though, the name of Lincoln Beachey will never die not after that Sunday afternoon when off Point Loma he made the world's first upside-down flight, the world's first loop, then returned and did them again. The people of San Diego, crowded on every hill that Sunday afternoon, cannot forget.

Or perhaps the age of mellowness at last is descending. For, surely, it can descend on a city the same as on a person. So many of us around here already are thinking fondly of aviation's past instead of concentrating on its present or its future. But that is the way it will have to be.

What formerly would make a front-page story, and get us all running over to North Island, today would not be mentioned, or enjoyed, or watched, or argued about or noticed. Nothing short of a hundred planes colliding all at once could compete today with San Diego's aviation stories of yesterday. A squadron of planes leaving San Diego this week for Honolulu receives less than three paragraphs, third page. Besides, the squadrons from San Diego are now making such flights all the time. And to Panama nonstop, also. The novelty is over.

Yet some of these old names in aviation on North Island deserve a trace of permanence, for the editions carrying some of their obituaries have long ago been used for wrapping fish, we shall say- Yet all these old-timers are not dead. Far from it. Some are still flying. Even they perhaps secretly cherish those old memories of North Island like some veteran trouper remembering the night so long ago when his juggling act was billed second instead of being the opener in the Palace,

All this accounts in part for the subsequent tossing of so many names at random into this bushel basket. For what these early men did on North Island for aviation at the risk of their shoulder blades in those rickety craft has not been exactly forgotten, although laurels since then have had a peculiar habit of drenching some fliers too much for their own good while forgetting others completely.

Lieutenant W. R. Taliaferro, during the August of 1915, established from North Island a new American endurance record of nine hours and forty-eight minutes. His fuel exhausted, he landed with a dead stick. Next month he was killed by a fall into the bay.

Next year, 1916, Captain C. C. Culver, in a plane near Los Angeles, sent radiotelegraph signals which were received on North Island. A month later he sent radio messages from his plane to a plane piloted by Lieutenant W. A. Robertson. These were the first instances on record in which radio was demonstrated as an absolute success in sending and receiving messages in the air.

The death of Lieutenant H. B. Post, who was killed while attempting an altitude record from North Island, February 9, 1914, is responsible for the pusher-type plane definitely being condemned by the army. He lost control of his plane. And the motor, being in back of him, fell on him.

This was one death too many of this sort for the army. But the condemnation of the pusher types left the school on North Island with only two planes.

But it is doubtful if any North Island class quite equaled that of 1915-17 in students who later became celebrities or who already were civilian celebrities before starting to fly.

This class included Major J. P. Mitchel, the one-time mayor of New York, after whom Mitchel Field, on Long Island, is named; Captain Roscoe Fawcett, of the Fawcett Publications; Norman Ross, then the world's swimming champion; Major W. R. Ream, one of the first flight surgeons of the army, who now has a landing field named after him close to San Diego;

Colonel T. C. Turner, who later became chief of the Marine Air Service; and there was Captain Henry H. Arnold, later Major General and chief of the Army Air Corps.

The list of that class could go on and on, but others among the class will be mentioned later, especially those who stayed with flying.

The list of that class could go on and on, but others among the class will be mentioned later, especially those who stayed with flying.But the next world event occurred in 1918-19 when Major A. D. Smith attempted a transcontinental flight to New York and return with five planes. These five planes, a record number at that time for such an attempt, flew from North Island to New York by way of Texas, Louis-iana, Alabama, Georgia, Florida and the two Carolinas. The fliers remained in New York a week and were the talk of the country.

Their return trip to San Diego went well until they reached El Paso, Texas. Here the planes, after landing, were struck by a violent wind. All except one were over-turned and damaged beyond repair. However, this was the first time in history that a formation of planes had flown from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

Another job handed North Island in 1919 was the formation of an aerial forest patrol. As radio communication still required too expensive an equipment and was not dependable, carrier pigeons were carried in each plane and released whenever a fire was sighted. This accounts for the pigeon lofts which remained for so long on North Island.

Lieutenant James H. Doolittle on September 4, 1922 flew from Jacksonville, Florida, to San Diego in twenty-one hours a record which stood for eight years.

The world's first refueling in midair was successfully attempted above North Island in 1923. The pilots in the plane were Lieutenant Lowell H. Smith and Lieutenant J. P. Richter, who thereby broke records for the combination of speed, duration and distance.

But this is getting ahead a little, for in 1917 the navy was granted authority to move in on North Island and occupy two old buildings and the Curtiss school hangar for seaplanes. This, of course, was the beginning of the present Naval Air Station and the beginning of the end of the army there. For the army on North Island is no more.

This was a hard gulp for the army, and it has never quite overcome the irony of the thing. But as a final fling, and to celebrate the Armistice, the army put into the air from North Island in 1918 the largest number of planes aloft at any time at one place in the United States. The planes numbered 212. They did not fly in the tight formations of today, but rather spread all over the sky, which made their number seem four times larger than that used in such flights today. This first big flight which brought newspaper correspondents to San Diego from all pointswas under command of Lieutenant Colonel H. B. S. Burwell

To attempt the first nonstop transcontinental flight, Lieutenant Oakley Kelly and Lieutenant John A. Macready had on North Island, in 1922, a thick-wing monoplane with a wingspread of ninety-six feet. But the gigantic ship (certainly gigantic for then) was powered by a single Liberty motor. The ship had never taken off with a full capacity, so the moment of take-off was something to see, and all of San Diego came out to see it.

After covering a half-mile of North Island before it could lift itself, the ship then was headed straight for the bluffs of Point Loma. The pilots were forced to bank at an altitude of a hundred feet. They circled North Island twice, then aimed for the mountains only to find the pass blocked by a fog.

The fliers then decided to circle back over North Island and try to break the endurance record. When they were again above the field they dropped a message to the com- manding officer requesting that he make necessary arrange- ments to authenticate the world's record if they should succeed. From then on they circled North Island for thirty-six hours and eighteen minutes, with the whole country following the news about them. But all for nothing.

For, despite the fact that the plane was watched by thousands during the thirty-six hours of circling, the record was not authenticated and was never allowed because of lack of official witnesses.

Although the fliers were disappointed about this, they started out on another nonstop transcontinental attempt as soon as the ship was reconditioned on North Island. A cracked water jacket forced them down at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indianapolis, but they had broken the world's record for distance flight. They had covered 2,284 and again were the talk of America and Europe.

The next event was the round-the-world flight which started and ended on North Island in i924. This flight, as we may recall, occupied 176 days. Lieutenant Lowell Smith was in command after the planes reached Alaska.

But in this haste to speak about records broken on North Island, or from North Island, the story has moved too rapidly into near-modern times. Sweeter is the feeling to return once again to those hedge-hopping days on the island when aerial charts were nothing more than railway maps obtained from the local railway station, when the few plane compasses were more misleading than useful, when beacons as yet were not so much as a futuristic dream, when emergency landing fields were unknown. But even then, almost from the start, these pilots on North Island were attempting to push their crates into the back country. To get carried by wind drift into the deserts of Mexico was easy, brutally easy, during an overcast sky. Some of the pilots, when lost, had no other alternative but to die after forced landings, and two others when lost from North Island were murdered by Tiburon Indians.

Lieutenant W. A. Robertson, with Colonel H. G. Bishop as passenger, started from North Island for Calexico. Without knowing it, they were going in the wrong direction. They flew to the limit of the gas supply, then made a dead-stick landing on what they thought was the shore of Salton Sea.

After walking south they turned around and retraced their steps. They noticed for the first time the presence of a tide, and that while walking south the water completely obliterated their tracks. They realized then that they had landed, not at Salton Sea, the California desert lake, but on the Gulf of California, Mexico.

They emptied a one-gallon can of oil and filled it with water from the radiator. With this as their drinking water they headed north with two sandwiches and two oranges. The nearest point to the United States boundary was sixty miles to the northeast, although they had no way of know- ing this then.

The country over which they tramped was entirely devoid of water and consisted of shifting sand dunes. They gradually discarded their helmets, goggles and aviation coats. The nights were cold, and during the day the men caught the full blast of the Mexican sun.

After eight days of this, Lieutenant Robertson stumbled into the camp of one of the automobile searching parties at a surveyor's tank on the border. He was out on his feet. He was placed inside the car and directed the driver back across the desert to find Colonel Bishop. The automobile became stuck in the sand dunes, and the party continued the rest of the way on foot, following Lieutenant Robertson's tracks.

Colonel Bishop was found thirty miles from the border but was too far gone to walk. An ambulance from Yuma managed to get within fifteen miles of him, and the rescuers carried him the distance.

Yes, those were the hedge-hopping days. Those are the days the men of San Diego remember when they look today across the bay at North Island. They remember because they took part in the searches.

In another case about the same time, four other North Island fliers were lost in Mexico but were saved from starvation by a herd of steers. These fliers were Lieutenant William R. Sweeley, with Corporal J. C. Railing as passenger; and Lieutenant Daniel F. Duke, with Lieutenant McCarn as passenger.

They had taken off from North Island for Prescott, Arizona. Confused by the weather and having no compass, they headed into Mexico by mistake. Lieutenant Sweeley ran out of gas and made a forced landing. Lieutenant Duke continued southward for some time and, seeing an adobe house, circled it and landed there. The house was empty, so he returned to where the first plane had landed.

He picked out the worst part of the valley and landed in a marsh. His plane turned over on its nose, breaking the propeller and one wing. The gasoline was transferred from the wrecked plane to the good plane, and a take-off was attempted. While trying to taxi to a smooth part of the field, Lieutenant Sweeley bounced into a large hole cov- ered with grass. The plane turned over onto its back, and that was the end of that.

The party of four was marooned without food and with no idea of the location, except that it must be somewhere in Mexico. The men limped from the wreck to see what they could find. In the distance they sighted a herd of cattle.

The fliers tried to separate a calf from the herd, but this stampeded the whole herd out of the valley and left the lost party as hungry as before. After dark Lieutenant McCarn and Corporal Railing succeeded in driving a steer into a blind canyon. There they cut its throat with a bearing scraper and returned to the wrecked plane with a quarter of beef.

The beef was boiled in a receptacle made from the aluminum cowling of the plane. They lived on this beef forever, it seemed, and then one day sighted a couple of Mexicans and were guided to the Circle-Bar Ranch. The owner of the ranch was an American. He got them out.

The two North Island fliers murdered by Mexican Indians were Lieutenant Cecil B. Connelly and Lieutenant Frederick Waterhouse. They were flying border patrol, from North Island in August 1919 and in bad weather confused the Gulf of California for the coast of California. They thought the west shore of the Gulf was the coast line adjoining San Diego. They followed the west shore of the Gulf southward deeper into Mexico, thinking they were following the San Diego coast northward.

Out of gas, they finally landed on the shore of the Gulf. Part of their story they themselves carved with a jackknife on the fuselage of their plane;

Flew four hours, five minutes. Turned to our right and flew up coast for two hours and 35 minutes. Didn't see a sign of civilization all the way. Saw boat here. Circled it and landed but it didn't see us. We have no food. Are drinking water from radiator. Tried to catch fish, but after two days gave it up. We have been here five days and are pretty weak. We will mark for days here on left of this sign. We started walking up coast for a day and a half. Ran out of water and turned back. . . .With marks they indicated the days, all told, as seventeen.

What really happened, according to facts found later, was that the men in the boat did see the plane. They were Indians off Tiburon Island, the last hold-out of the once- famous tribe of Sens. The Indians sighted the fliers, all right, and after a while came ashore and joined them. One of the fliers was in bad shape and unable to walk. They had been living on clams and crabs.

The Indian fishermen (not in a boat exactly, but a blue canoe) carried the fliers south in the canoe to the Bahia de los Angeles and landed them there, later returning and killing them. The Indians robbed the bodies of money, took what clothing they wanted, then left.

The actual fate of the missing lieutenants was not known on North Island until October 1919. The word came after a seaman had reported to the American consul at Nogales that the bodies of two men had been found partly buried at the Bahia de los Angeles. The destroyer Aaron Ward was sent immediately south from San Diego, found the bodies, and returned with them to San Diego. The rest of the story was pieced together bit by bit aferwards, as such things are, by more and more evidence and by a confession from one of the Indians.

Today, after thirty years, one cannot help wondering how many lives North Island has given to aviation. The list, even if it could be checked in full, would be too de- pressing to record certainly too depressing to record on a monument. Nor do fliers, as we know, care to look at their business that way, especially those who experimented with North Island's first rickety crates. Other industries rail- roading, mining, chemistry have taken their first big tolls, too. Mining, especially, is still taking its toll.

Yet all this is a rough story of the island which is not technically an island, but which dominates San Diego's harbor and remains the central ring of the aerial circus continually under way.

San Diego has other flying fields, of course, including the huge Lindbergh Field adjoining the bay and built from harbor dredgings.

Naturally we recall the time when he was having his "Spirit of St Louis" built here inside a former tuna cannery reconverted into a plane factory. And naturally we remember how naive he seemed and that he actually wanted letters of introduction to carry to Paris, and that he wanted to know ahead of time the cheapest way of reaching Paris from the landing field outside the city and if an interurban was running to Paris from the field, and that he wanted to know if, by selling his plane over there, he would have enough money to see a little of Europe and pay his fare back home, too. He was afraid the plane would not sell for much over there because of the depreciation of the flying-hours. Yes, we remember all these conversations because we were around the plane factory and took part in them.

Naturally we recall the time when he was having his "Spirit of St Louis" built here inside a former tuna cannery reconverted into a plane factory. And naturally we remember how naive he seemed and that he actually wanted letters of introduction to carry to Paris, and that he wanted to know ahead of time the cheapest way of reaching Paris from the landing field outside the city and if an interurban was running to Paris from the field, and that he wanted to know if, by selling his plane over there, he would have enough money to see a little of Europe and pay his fare back home, too. He was afraid the plane would not sell for much over there because of the depreciation of the flying-hours. Yes, we remember all these conversations because we were around the plane factory and took part in them.But it so happens that some of us do not share in this national habit of picking out one symbolical hero at the cost of the memory of all other nervy men in the same business, men who not only are forgotten now but a good many of whom are dead from their own experiments. Be- cause of North Island's thirty years, San Diego has seen too many great and courageous and hard-working fliers for the city to be sold completely on one personality as the outstanding deity of them all. And so all of North Island remains San Diego's symbolical personality for aviation. And it will have to be like that. For too many seasons now, too many springs, summers and winters, has the city watched the experimenting planes go up and come down- sometimes altogether too fast. The island's crash siren sounds. The ambulance and fire truck speed from the garage, and the families of the officers' quarters over there are meanwhile left wondering: "Who?"

And maybe someday, centuries from now, historians on this same harbor, in looking back, will change the question from "Who?" to "Why?"

Labels: aviation, curtiss, Ivar T. Mayerhoffer, Joe Boquel, north island, San Diego

• A Thousand Words

The lineboy who helped push our C-45 into the hangar this morning commented that his boss's Dad had flown B-24s. I said there was good chance he'd flown a C-45 at some point in his training. Boss shows up with his Dad's log book including a 7.3 hour entry on 5/31/44 for the mission to Ploesti flying 'Sloppy Joe', which brough him home—unlike many, many of the other aircraft and their crews. The two pictures tucked in the loghbook, and the markings on the inside back cover, tell the rest of the sad story. (Click image to enlarge.)

While he climbed up into the cockpit I laid the logbook on the hangar floor and took this image. It shows he started out flying Stearmans in California, then BT-13s, then the Cessna AT-17 'Bamboo Bomber' (no C-45 time). With 261 hours he climbed into the right seat of a B-24 at Kirkland Air Force base in Albuquerque NM. After 12 hours of training, he helped fly B-24J 'Double Trouble' to England, and after another 22 hours (3 missions) was flying as aircraft commander (age 24, total time 295 hours). With 18 missions to go they were shot down on 8/22/44 over Hungary.

Anyone care to hazard a guess what the drawing at the bottom might be? I have no clue.

Labels: B-24, b-24 bomber, Beechcraft, C-45H, usaac, USAF, WW2, WWII

• Flying the Unfriendly Skies

It is a typical day for the flight attendants aboard American Airlines Flight 710, a 737-800 headed from Dallas to New York with a scheduled departure time of 9:05 a.m.

As Debbie Nicks, 56, works in the first-class galley, brewing coffee and hanging up passengers' jackets, she glances down the jetway and notices a crush of people at the gate. An earlier flight to New York has been canceled, and people from that flight are desperate to get on this one. It is a familiar scene these days, what with many planes flying at near capacity, and so Debbie just continues her regular routine, making the announcement to passengers onboard that they should make sure all carry-on luggage is stored either in the overhead bin or below the seat in front of them.

Back in coach, Anna Wallace McCrummen, 45, organizes the cart of drinks and food for sale that would later be pushed down the narrow aisle, then takes a blue rubber mallet to whack a bag of ice cubes that had frozen into a solid block. She hits it over and over again, perhaps a little too keenly, as the sound - thwop, thwop, thwop - echoes off the walls of the small galley.

Meanwhile, in the main cabin, Jane Marshall, 50, walks down the aisle, checking to make sure people are finding their correct seats, keeping an eye out for passengers who have sneaked on luggage that she knows won't fit in the overhead space and trying to defuse any tense situations before they escalate into crises. But perhaps it is already too late. Two women who have been double-booked stand sulking in the aisle, wheelie bags firmly planted by their sides, signaling that they are not about to budge.

"What a mess," mutters Jane once the double-booked women have been found seats and the line of stand-by passengers is turned away from the gate. Only then, after every seat is taken, overhead bins shut, electronic devices stored and seatbelt sign on, do the three women finally settle in to their jump seats for one of the few moments of respite during their workday.

Over the next 11 hours, they will fly from Dallas to New York and back again, a routine that is clearly second nature to them. In all, the three represent nearly 70 years of flight attendant experience.

And today I am one of them.

In a behind-the-scenes look at the other side of air travel, I donned a navy suit and starched white shirt earlier this summer and became a flight attendant for two days. With the cooperation of American Airlines, I first went to flight attendant training school at the company's Flagship University in Fort Worth, Tex., where I learned what to do in an onboard emergency, from how to open an emergency exit window on a 777 aircraft (it's heavier than you may think) to operating a defibrillator (there are pictures to help you get the pads in the right place). I then flew three legs in two days: a round-trip journey between Dallas and New York, and then back to New York the next day.

And though the other flight attendants knew I was a ringer, the passengers did not. Thus I got a crash course in what airline personnel have to put up with these days - and, after just one day on the job, began to wonder why the phrase "air rage" is only applied to passengers. Believe me, there were a few people along the way, like the demanding guy in first class who kept barking out drink orders as the flight progressed (until he finally passed out), whom I would have been more than happy to show to the exit, particularly when we were 35,000 feet in the air.

WHAT'S it like to be a flight attendant these days? That's what I've often found myself wondering as I sit in my seat, waiting impatiently as yet another flight is delayed and my connection threatened, while around me are passengers fighting with each other over the lack of space in the shared bin, or complaining about having been bumped from an earlier flight, or swearing "never again" to fly this specific airline because they have been stuck in a middle seat even though they booked their ticket six months ago.

Is there a less-enviable, more-stressful occupation these days than that of a flight attendant? Just the look on their faces as they walk down the aisle - telling passengers that no matter how many times they try to squeeze them in, their suitcases are not going to fit into the overhead bin, or explaining yet again that they will not get a single morsel of decent food on this three-hour flight - tells you all you need to know of their misery.

It was a feeling that was reinforced when I glanced at an Internet chat board for flight attendants, airlinecrew.net, and came across postings like this: "I've been a flight attendant for 6yrs now, and I can tell you this much - if I'm still a flight attendant in 20yrs, I'll be a raging b*tch!"

It wasn't always this way, of course. Back in 1967, the best-selling book "Coffee, Tea or Me?" (subtitled "The Uninhibited Memoirs of Two Airline Stewardesses") portrayed life in the air as a nonstop party, one to which the authors felt privileged to be invited. Another 60s artifact, the play "Boeing, Boeing," recently revived on Broadway in a Tony Award-winning production, also pictured the life of stewardesses (as they were called then) as a glamorous romp, with suitors in every port. Most recently, the fictional ad executives on "Mad Men" were thrilled when they were asked to compete for an airline account, not only because of the business it would bring in but also because they would be in on the casting sessions for the stewardesses and would get to fly free. Oh, such fun!

It's a fair bet that nothing about air travel today would inspire such rapture.

In fact, the flight attendants I spent time with on my three flights took a grimly realistic view of their jobs, aware that temper flare-ups - "People just get nasty," said Jane Marshall - are in some ways an understandable reaction to the process that passengers themselves have to endure in trying to get from one place to another. "After they've been harassed by security, we're the ones they see," said Debbie Nicks, explaining why a minor inconvenience, like being told that there are no more headsets, might send someone into a fit. "Your shining personality only goes so far," added Jane.

Certainly the one lesson I learned quickly - along with how to cross-check the doors and that Dansko clogs are the footwear of choice among experienced flight attendants - was how to say "no" politely. No to the young Indian man who asked for a blanket for his mother who was shivering in her sari next to him. (There were none left.) No to the hungry passenger who wanted to purchase a cookie. (We had already sold the only two stocked for the flight.) No to the guy who, like many of his fellow passengers, was concerned he wouldn't make his connecting flight because of our late departure and pleaded, "Can you call and find out?" (Sorry, but here's the customer service number you can try when we land.)

I also got a crash course in stress management.

My return flight out of La Guardia was as packed as the morning one out of Dallas, and the passengers were even crankier. The plane was supposed to take off at 4:25 p.m., but at 5, passengers were still boarding, with many already anxious about whether they would make their connecting flights.

Meanwhile, two commuting flight attendants came aboard to ride in the jump seats. Jennifer Villavicencio, 35, a mother of two from Maryland, had been up since 5 a.m. working a four-leg trip - New York to Chicago, Chicago to St. Louis, St. Louis to Chicago, Chicago to New York. As a newer flight attendant on "reserve," she largely works on call. She spends days at a time away from her children, sometimes leaving them with her mother in Dallas, while she works out of New York. In between shifts, Jennifer shares a four-bedroom crash pad in Queens with other flight attendants. She sleeps in a so-called hot bed, bringing her own sheets and grabbing whichever of the 26 bunks is available when she arrives.

"I like the top bunk," she said, "because you can sit up all the way."

Our chat was interrupted by some news from the gate agent: The plane might be shifted to another runway. "Oh, good, more drama," said Anna, explaining to me what was about to happen. "When it's midsummer and it's hot, and the runways are short, you can't have a certain heaviness or you can't take off. Because we're switching runways they're going to put a weight restriction on and they're going to pull people off because of the weight."

Jennifer sprang to attention. As a commuter, she knew her seat would be among the first to go if the flight was deemed too heavy for the new runway. She began counting the number of children onboard, a factor that could immediately minimize the weight issue, if there were enough of them. Thankfully, there were 11 - enough to save other passengers from being taken off.

At 5:49 p.m., the plane finally took off, more than an hour late.

I had been told that working first class was harder than coach, and so I joined Debbie at the front of the plane. When I arrived, Debbie had already taken down the passengers' drink orders, her neat handwriting listing 3A - BMary, B - RW, E -Vodka tonic, etc., on a pink cheat sheet posted on a cabinet. She warned me that Passenger 4B, a heavy-set young man with an iPod, was already proving to be a handful. He had taken some sort of painkiller for a bandaged wrist when he boarded, immediately followed by a Jack and Coke, followed by a Heineken, and now wanted a glass of wine, not in one of those standard-issue wine glasses, but in a fat cocktail glass instead.

I recalled what one flight attendant had told me when I asked about what they do when it looks like a passenger is having too much to drink: Water it down. In coach, where travelers mix the drinks themselves, some attendants invent their own rules - "I can only sell you one drink an hour."

First class was intimidating. And I, frankly, wasn't much help, finding all I was really qualified to do was hand out and collect the hot towels. Debbie, however, performed a series of in-flight culinary maneuvers so demanding it inspired a challenge on the Bravo television series "Top Chef": Prepare an edible, multicourse meal, mid-air, in a narrow hallway, between two ovens at 275 degrees and a hot coffee maker.

As the flight wore on, Passenger 4B finally dozed off; dessert was served and the flight attendants became weary. Jennifer, who wasn't even on duty, had taken pity on a mother with a screaming child and was walking him up and down the aisle on her hip. Later, she would occupy a toddler by letting him hold the other end of the trash bag as she collected garbage from passengers.

The flight arrived in Dallas at 8:02 p.m., 52 minutes late. Debbie, Jane and Anna would be paid for the actual flight time of roughly eight hours for the two legs of the round-trip journey. They would also receive a per diem of $1.50 for every hour they were away on the trip. (For certain delays, American said its flight attendants receive an extra $15 per hour, pro-rated to the actual time, minus a 30-minute grace period.)

Flight attendants' schedules are often wrecked by delays and as the airline industry went into its steep downturn after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, many airline workers took significant pay cuts and reduced benefits in order to help the carriers stay in business.

There are roughly 100,000 flight attendants in the United States, according to the Association of Flight Attendants, down from about 125,000 in 2000. Depending on the airline, attendants earn between 7 and 20 percent less today than before 9/11, according to the association. The average flight attendant salary today is around $33,500 a year.

There are already fewer attendants working each flight. Most carriers now go by the minimum number required by the Federal Aviation Administration - one flight attendant per every 50 passengers. And though the benefits, like free flights for your entire family, still exist on paper, they are hard to claim as airlines continue to pack planes full of paying passengers. In other words, it's not much fun anymore.

Certainly, it's a far cry from the "Coffee, Tea or Me" years.

"Who would have thought, after 30 years, that we'd be a flying 7-Eleven," Becky Gilbert, a three-decade veteran of the industry told me during a break in our training session in Fort Worth. "You know, I mean we used to serve omelets and crepes for breakfast, and now it's 'Would you like to buy stackable chips or a big chocolate chip cookie for $3?' "

When Anna, Jane and Debbie became flight attendants more than 20 years ago, tedious chores, like collecting passenger trash, were offset by the perks and quasi-celebrity status that came with the job. "When you walked down the terminal, all the people would look at you," said Jane, between bites of pizza on a lunch break at La Guardia, her back turned to a group of travelers paying no mind to her navy blue suit, her gold wings or the black roller bag by her side.

"People used to," continued Debbie, a well-groomed flight attendant with cropped gray hair and gold accessories who can finish Jane's sentences after 23 years of flying together. "What girl didn't want to be a stewardess?"

"It was the layover in the old days that made it glamorous," Anna explained. "You worked one leg to San Diego and you were sitting on a beach, margarita in your hand, and you were going, 'I'm getting paid to sit here.' That was the old days. Now, we're like crawling into bed thinking, 'I hope my alarm goes off.' "

Luckily, the next morning at 4, mine did. Running on no more than five hours of sleep and no coffee, as the hotel takeout stand had yet to open, I caught the five o'clock hotel shuttle to the airport. After stumbling through security I arrived at the gate, an hour before departure, as required - bleary-eyed and beat. When I met the crew I would be working with, a jovial bunch who often fly together, I warned them that I might be useless.

They could empathize. David Macdonald, 51, an American flight attendant for 28 years, was on his fourth straight day of flying. Elaine Sweeney, 55, who has worked for American for 30 years, was on her third day. And Tim Rankin, 56, a 32-year veteran, was on his third flight in 24 hours.

Standing in the aisle of the cramped MD-80, Elaine assured me that the passengers, mostly business travelers, would be relatively well-behaved. "It's so early on this one," she said, "that usually half of them go to sleep."

As with the flight attendants I worked with earlier, my new companions described their job as being one where they constantly had to calibrate the mood of the passengers. "Over a typical month," said Tim, "I will be a teacher, I will be a pastor, I will be a counselor, I will be a mediator." As he slid his 5-foot-11-inch frame into the sliver of space between the cockpit and the first-class bathroom, he slumped into the jump seat and let out a barely audible sigh. "I'll have to tell people that a two-and-a-half-foot-deep bag will not fit in a one-and-a-half-foot hole," he said.

"People need to understand that the rules of social order do not go away when you get on an airplane," Tim added, his Texan twang kicking up a notch as he laid down his commandments. "You cannot have sex on an airplane. When you purchase a ticket, that does not give you the privilege of yelling at me. It does not give you the privilege of sitting anywhere you want to sit. They assign you a seat. I do not have an extra airplane in my pocket if my flight's delayed."

Elaine chimed in, "We joke that people check their brain when they board."

When we landed in New York at 11:04 a.m., I was wiped. Standing for the majority of the flight, which included a brief bout of turbulence, had unsettled my stomach and caused me to lose my appetite. My feet hurt. I had lost all feeling in my pinkie toes.

Before we disembarked, Tim, in a touching gesture, ceremoniously gave me his gold wings. I then dragged myself through the terminal, past a throng of restless passengers gathered around the gate, anxiously waiting to board the plane.

I was glad I was heading home.

By MICHELLE HIGGINS

New York Times

9/14/2008

Labels: airlines, flight attendent, stewardess

• On A Wing And A Swear

It was a dark and stormy night. A shot did ring out. But, frankly, I wasn't thinking about clichés when the .45 slug ricocheted past the wing of the Cessna 185 I was about to lift off a muddy dirt road in the mountains of northern Mexico back in the early ‘60s.

It all started when a Texas oilman called me in Mexico City to see if I could help him rescue his daughter. "Not exactly the Lord's work," I observed, trying to preserve my cover as a missionary. The company I worked for in Langley, Virginia didn't take kindly to it's employees freelancing, but then maybe this was their idea.

"Not exactly, “ the Texan drawled. "But you have a plane, you speak Spanish, and you know your way around the mountains of Mexico. The bastard that married my daughter is actually holding her prisoner, and he beats her. Besides I have the means to make a nice contribution to a charity of your choice, say a local church,” he said with more than a hint of sarcasm. So much for my cover.

Seems the Texan desperately wanted an heir, which his daughter and only child had provided with the help of the rich Mexicano she'd met a few years earlier. But it also seemed that said Mexicano was not exactly the kind of husband Daddy had in mind for his little girl. For that matter, said Mexicano was not exactly the kind of husband Daddy's little girl wanted either.

The Señora's maid confirmed her mistress screamed in pain when EI Jefe came home boracho, which was often. And, yes, she'd do anything she could to help Doña Juanita escape. She loved little Esteban as if he was her own; and the Señora, well, the Señora was always very kind.

They lived in a large house with large walls, the latter but not the former, common in Mexico--about 3 feet thick and twelve feet high with broken glass embedded in mortar along the top. There was no airport nearby, but the house sat on the outskirts of a village alongside an east-west secondary highway, which meant that although the road was dirt it was in relatively good repair, and not heavily traveled.

Wouldn’t be the first or last time I'd landed on a road. The only real obstacles would be a single set of power or phone lines strung across the road into the house, a line of trees and power lines on the south side, and parallel fences along both sides. And the narrow concrete bridge 1200’ down the road. Afternoon thunderstorms that carry into the evening could be an issue, and density altitude would definitely be a factor.

So the plan was to fly in posing as a friend, offer to take mom and kid for a pretty sunset sightseeing flight, and then beat feet for the the border. The only tricky part was that since El Jefe refused to let his wife return to the States, he presumably wouldn't take kindly to her being whisked away even briefly. Certainly his behavior while "under the influence" suggested caution, but the flight didn't look like anything dangerous. Lord knows I'd landed on roads all over Mexico and Guatemala the last few years, and the flight back to the states was something I'd done many times.

The weather on the trip up was typical: scattered to broken Cu at 9000 with build-ups over the mountains. On the windward side of the mountain ranges there was good ridge lift so the ride was bumpy but faster than usual. At one point I even had to pull the throttle all the way off. We were going up 1800 FPM and pushing red line while I pondered how to slow down to maneuvering speed and not go up 2500 FPM into the clouds.

A thunderhead looked like it was headed for town, and it was starting to get gloomy when I arrived overhead. I made a low pass over the house—no advantage in sneaking up, the plane would attract lots of attention—and checked to make sure the road was as advertised. It was. The landing was uneventful, and I taxied into an empty lot across the highway from the house. As I pulled the mixture to idle-cutoff things started to get interesting.

Doña Juanita exploded out of the front gate running with her little one cradled in one arm. She looked for all the world like Tony Dorsett on an end run, except for the long skirt. Mixture rich, prop up, throttle cracked. Hit the ignition switch. Come on baby, this isn’t the time to give me trouble with a hot start.

The maid came charging through the gate running barefoot every bit as fast as La Señora. They were headed for the plane and, I suddenly realized, straight for the nearly invisible prop.

Throttle to the firewall, yoke forward, stomp on a brake. As the plane lurched forward onto the road and then spun around sideways, in a strobe flash of lightning, I caught a still-frame of a man bounding from the house shoving a clip in the butt of an automatic.

Mom lateraled the baby to me through the door and got one knee on the floor in the back seat. The maid dove in behind her head first, and was struggling to her knees when the proverbial but very real shot rang out. And it started to pour.

The engine backfired, then roared, as I firewall the throttle. Doña Juanita, was crawling up front falls over and partway out the door, grabs. She grabs the yoke. Swerve. Grab her by the arm and yank her in, screaming. Accelerating. Slowly. The Mom, tjhe maiod, and baby are all screaming. Lean the mixture for density altitude—must be over 8000. Tail's up but we're sure not goin' faster than a speeding bullet. More rain, can't see much through the windshield. Add a notch of flaps. Stagger into the air. Stall warning chirps. Barely climbing. Drop a wing and ease around the bridge. Fly down the riverbed. Door latched. Rain stops. Lightning behind illuminates the hills. A sliver of moon appears between the clouds. Count heads. Hell of a ride.

Long-range tanks, a few gentle words, a dark night, a little nap-of-the-earth (only they didn't call it that back then), and howdy y’all, we’re over Texas. The hard-working drug busters with their E-2s and UAVs and infrared eyes wouldn't come along for another thirty years. We didn't complicate things by stopping to chat with the immigration boys at the border, in any event.

The trip south was the same low-level boot-scootin’ boogey except for the truck going the opposite direction that crested a hill the same time we did just south of the border. The way the driver's mouth was working it looked like he was yelling something about "Chicago Putin Monday" as we flashed overhead. I knew what he meant, but then missionaries aren’t supposed to be able to swear in Spanish.

Navy folks often end sea-stories with, “This is a true story. No shit." In this case, the names and a few details have been changed to protect the guilty. Other than that, this is a true story. No shit.

Labels: cessna, cessna 185, cia, Guatemala, Mexico, missionary

• Line Division

I’ve often thought of the men I was supposed to lead back in the Vietnam War era when we were on the U.S.S. Constellation (CVA-64) operating from Yankee Station. Attached to VAQ-134, I was a Junior Officer and pretty worthless as the Line Division Officer. But I was smart enough, at least, to get out of the way and let the Chief run the show. Still, I admired those young men—average age probably around 19—and I appreciated what they were doing.

I just ran across an old squadron ’Famly Gram’ news letter from September 1973, just before we headed home. In retrospect, I doubt what I wrote gave wives and girlfriends much comfort, even if it did show them their men were doing something exceptional.

Do you ever wonder what's going on up on the roof? Probably not, but then your roof is a little different from mine. I often wonder what's going on up there - up on the Flight Deck.

My roof is a place with noise so loud it is literally deafening. It comes from jet exhausts that blow scorching 150 degree winds of over 100 miles per hour even when you’re yards away. Sometimes those winds, whipped to several hundred miles per hour by the power required to taxi an aircraft, have flicked men over the side to the rushing water 60 feet below.

Intakes from the jets on the roof are great grinning monster maws that have already sucked up one man's life when he ventured too close. And propellers. Great heavy spinning scyths, swinging in whicked arcs that sound like hell, and can take you there in a brief gory instant.

That's not all that's going on, up on my roof. There are men working in that nightmare world. And they work in tropical sun, torrential rain , and dim erie red light at night. Ask an average man to go up there, and you know what he'll tell you? "No way, man."

But men do work up there; the men from the Garuda Line Division do. More than twelve hours, day and night. Seven days a week, sometimes for almost a month without a break. You know how they tell it's Saturday? It isn't a ball game on TV, or a barbecue out back with the kids. It isn't an extra beer or two 'cause you don't have to work tomorrow. It's Saturday because, because. . . well, you can't tell when it's Saturday. "What day is today anyway?" "Hell, I don't know, September I guess."

Who are they, those men that live among the seventy-odd beasts that so casually can cut them down for a moment, for just the tinyest, briefest moment of inattention? A brown shirt. A plane captain, one of those guys from the Line Division I was telling you about.

He comes in a variety of shapes and sizes (check out "Sugarbear" if you don't believe me). They're called Duke, Wayne, Inspector Ben. Hobber, Bruce, Gil, Newt, Beetle, Rat Bun (Rat Bun?), Herbie, Lou, Dave, Taco, Dan, Grif, and Ike. They're called other names too, more often than not unprintable. Pick anyone at random and he probably has a mustache or beard, hair that's too long according to the MAA, no stencil on his pants from working on non-skid decks and very-skid aircraft. He has grease in his hair, and at least a bump or two on his head from pumping up that damn birdcage.

Who is he? He's from the Line Division. He's a man doing a hard job well. He's hot, thirsty, horny and harrassed.

He's a Garuda Plane Captain.

Labels: cva-64, EA-6b, garuda, Line Division, military, navy, prowler, USS Constellation, vaq-134

• A Strange Tale

In the Navy, tales are often prefaced with the statement, “This is a no-shit story,” which of course immediately makes its voracity suspect. This, however, is not such a story. While I can’t personally vouch for all the details, I can say that these are the facts as I know them unless stated otherwise. Those facts that I can’t speak for are from sources I trust completely.

Part The First

A Cessna Citation crashed January 24th, 2006 at Palomar Airport (KCRQ sometimes also referred to as CLD) killing three people and the pilot. The NTSB report reads as follows:

NARRATIVE: Citation N86CE departed Sun Valley (SUN) at 05:50 MST on a flight to Carlsbad (CLD). The airplane climbed to its assigned cruising altitude of FL380, which was reached at about 06:06 MST. The descend for Carlsbad was started an hour later, at 06:06 PST. Air traffic control cleared the flightcrew for the ILS approach to runway 24, which was 4,897 feet long. The flightcrew then reported that they had the runway in sight, cancelled their IFR clearance, and executed a VFR approach in VFR conditions to the airport. The reported winds favored a landing toward the east, onto the opposite runway (runway 6). During the approach, after a query from the first officer, the captain indicated to the first officer that he was going to "...land to the east," consistent with the reported winds. However, the final approach and subsequent landing were made to runway 24, which produced a six-knot tailwind. During the approach sequence the captain maintained an airspeed that was approximately 30 knots higher than the correct airspeed for the aircraft's weight, resulting in the aircraft touching down about 1,500 feet further down the runway than normal, and much faster than normal. The captain then delayed the initiation of a go-around until the first officer asked if they were going around. Although the aircraft lifted off the runway surface prior to departing the paved overrun during the delayed go-around it impacted a localizer antenna platform, whose highest non-frangible structure was located approximately 304 feet past the end of the runway, and approximately two feet lower than the terrain at the departure end of the runway. The aircraft continued airborne as it flew over downsloping terrain for about 400 more feet before colliding with the terrain and a commercial storage building that was located at an elevation approximately 80 feet lower than the terrain at the end of the runway. The localizer antenna platform was located outside of the designated runway safety area, and met all applicable FAA siting requirements. PROBABLE CAUSE: "The captain's delayed decision to execute a balked landing (go-around) during the landing roll. Factors contributing to the accident include the captain's improper decision to land with a tailwind, his excessive airspeed on final approach, and his failure to attain a proper touchdown point during landing."

A friend, who is also a United 757 pilot, watched the landing from a passenger seat on a commuter airliner as he headed for LAX before a flight to Singapore. Sitting on the right side of the aircraft, he watched a Citation ”dive bomb the approach lights,” and noted that it seemed extremely fast as it crossed the threshold. The commuter taxied into position, but then exited the runway instead of taking off. As they taxied clear he saw the smoke at the departure end, and knew what happened. He talked with the commuters flight crew briefly, and then called us with his story a few minutes later while driving to work at LAX.

Part The Second

One of our pilots brought in a photocopy of (I believe) a Business & Commercial Aviation article written by a corporate pilot. Seems he was IFR holding near Aspen, working his way down the stack, and was stunned to hear a Citation call in VFR requesting landing clearance. The next day, in the FBO’s crew lounge he heard a pilot call Flight Service with the same N-number. After the call, the writer asked the pilot if he was the one flying the day before, and if so, how did he manage to get in VFR. The pilot said he was indeed the pilot, and bragged that he often used a special route through the mountains under the clouds to sneak in. The writer commented that what the pilot described would have violated a number of his company’s procedures not to mention several FAA regulations. The article concluded with the moral that taking such chances will eventually kill you—as it did in the case of this pilot and three other people at Palomar Airport when the Citation he was flying went off the end of the runway and burned.

Part The Third